Art and Mathematics

The art and mathematics inspire each other:

building sculpture inspires new insights into the mathematics, and mathematical understanding inspires new

sculpture. Second, it is harder to get stuck: if the mathematics becomes too difficult to solve, we can switch

to illustrating the difficulty visually, and if a sculpture becomes too difficult to build, we can switch to

developing a basic mathematical understanding of the structure to be built.

We have been experimenting with variations of this circular hypar for several years, as it naturally

extends the hypar. On the mathematical side, the curved creases seem to behave quite differently from the

straight creases of the hypar, as the resulting origami seems to actually exist . A natural goal is curvedcrease origami design: can we harness the power of these self-folding curved-crease forms to fold into

desired 3D surfaces? How can we control the equilibrium form, and what (approximate) surfaces are even

possible?

Leonardo da Vinci may be best known for his painting and artistic works, but he considered himself more a scientist than an artist. He saw everything through the eyes of mathematics...including his drawings and paintings.

Leonardo received only basic instruction in reading, writing, and mathematics. His artistic talents must have been clear from an early age though, because around age 14 Leonardo began an apprenticeship with local artist Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence. There he learned not only drawing and painting, but also carpentry, leather work, and metalwork—all of which would be used by Leonardo as his interest in science and mechanics grew.

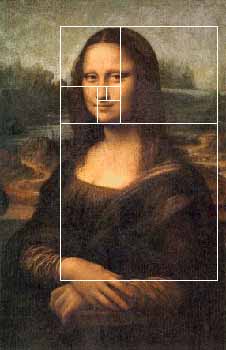

Mona Lisa and the Golden Ratio

Many scholars believe that Mona Lisa, probably da Vinci’s most famous and recognizable work, shows evidence that da Vinci may have used the golden ratio in many of his paintings and drawings. What is the golden ratio? The simple answer is that two quantities are in the golden ratio if their ratio is the same as the ratio of their sum to the larger of the two quantities.

Da Vinci never wrote specifically about using the golden ratio when painting Mona Lisa, but it’s clear that the painting adheres to the golden ratio in at least two ways, as shown below.

The important relationship of mathematics to art cannot be understated when discussing Leonardo’s later work, and in numerous documents, letters and notes, the relevance of this is well documented. At times, he seems obsessed with these issues: while working on Mona Lisa for example, Leonardo is reported by Fra’ da Novellara to be concentrating intensely on geometry.

The important relationship of mathematics to art cannot be understated when discussing Leonardo’s later work, and in numerous documents, letters and notes, the relevance of this is well documented. At times, he seems obsessed with these issues: while working on Mona Lisa for example, Leonardo is reported by Fra’ da Novellara to be concentrating intensely on geometry.

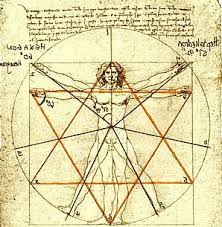

Why is this important? To Leonardo, and other Renaissance masters, the ‘Golden Ratio’ became a critical instrument in the matter of accurate proportionality. Fra’ Luca expounds the theory in 1498, while teaching in Milan, and later, in 1509, he and Leonardo collaborate to publish De Divina Proportione, in which is seen one of the most famous drawings associated with Leonardo: ‘Proportion Man’, also known as ‘Vitruvian Man’, which has become one of the world’s most iconic images. In the meantime, when the French finally re-occupy Milan in 1500, they take from Leonardo’s circle the Ferrarese architect, Giacomo Andrea, who had interpreted and translated some of Vitruvius’ work for Leonardo, and subsequently have him publicly beheaded and quartered on May 12, silencing a vital voice of science and independent thought. The message is not lost on Leonardo, who loses little time in diverting his loyalties to the French. At the same time, one can sense Leonardo disguising his own new-found knowledge in painting techniques that manifest themselves in his later works.